| Ba'al Shem

Tov (c. 1698-1760)

|

|

Rabbi Israel ben Eliezer is widely considered

to be the founder of the Hasidic movement, revealing himself

and assuming the name Ba’al Shem Tov (‘Master

of the Good Name’) in 1734 while living and teaching

in Tluste. It may be assumed that the many years he spent

in Tluste were influential in shaping the course of Hasidism,

described as the most popular mass-movement in Judaism

today.

While details of the Ba’al Shem Tov’s personal

life are somewhat obscure and subject to differing interpretation,

that he is an enormously important figure in Jewish history

is not disputed. |

He is arguably among the greatest Jewish figures who ever

lived, mentioned in the same breath as Maimonides, a 12th

century philosopher and scholar, and Theodor Herzl, credited

by many as the founder of modern Zionism in the late 19th

century.

The Besht (the commonly used acronym for Ba’al Shem

Tov) has been described as follows:

“There are probably more tales and legends told about

Rabbi Yisrael Ba'al Shem Tov than about any figure in Jewish

history…” (1)

“the Baal Shem Tov's influence on all religions in

the 20th century matches his enormous influence on Jewish

devotional practice in his own age.” (2)

“his teachings brought about a whole movement which

emphasized the idea of bringing God into all aspects of

one’s life, particularly through intense prayer and

joyous singing.” (3)

He emphasized “the power of each individual soul;

the concepts of love of your fellow; serving God with joy;

Divine Providence and perpetual creation.” (4)

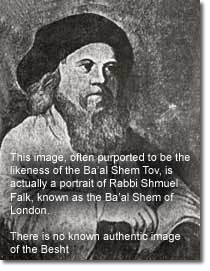

As the photograph accompanying this article points out, there

is no authenticated image of the Ba’al Shem Tov –

the one that is commonly presented as being his likeness is

actually a portrait of Rabbi Shmuel Falk, the Ba’al

Shem of London (5).

The Besht’s connection to Tluste

is confirmed by various sources.

First, two of the rare surviving letters that he personally

signed indicate Tluste as his home or place of origin

(6);

second, there are two specific references to Tluste

in the tales of his life and deeds, depicted in Shivei

Ha-Besht: In Praise of the Baal Shem Tov

(7); and, third, his mother is buried in the Jewish

cemetery of Tluste/Tovste, where her tombstone could

be found at least until April 1944. (8)

|

|

|

A brief biography

Much of the biographical information on the Ba’al Shem

Tov is derived from legendary tradition, and there is a vast

literature upon which to draw. One of the Besht’s followers

complied an anthology of 230 stories or shevahim (praises)

concerning his amazing life and works, which was published

in 1814 (9).

As the Besht himself left behind few if any of this own writings,

we are left to discern fact from fiction from what others

have written, a task that is fraught with difficulty. As Heppenheimer

notes (10),

there is a popular saying that runs: “One who believes

all the stories told about the Ba'al Shem Tov is a fool; one

who does not believe they could have occurred is an apikoros

(heretic).”

| It appears to be generally

accepted that Rav Israel was born around 1698 in the village

of Okopy (often written as Okup), in Podilia province

of what was then Poland. For ease of reference, Okopy

(48°32’ N; 26°24’ E) is situated about

5 km northwest of Chotyn, in present-day Ukraine, roughly

two-thirds of the way between Chernivtsi and Kamyanets-Podilskyy.

Curiously, despite numerous references to Okup (or Okopy)

in accounts of the Besht that I came across on the internet

while researching this article, not a single one precisely

pinpointed where this village is actually located. |

|

Where

exactly is Okup (Okopy)?

Okup has been variously described as being “near

the Dniester River” (11);

“on the Russian-Polish border” (12)

and “near Brody” (13),

which lies about 100km east of L’viv, far

from the putative location. The most specific reference

observed (in Heppenheimer) states that “Swiety

Trojcy, to give Okup its Polish name, had been founded

as a military outpost close to the Polish-Turkish

border…” (14).

more

»

|

|

According to tradition, Rav Israel’s parents –

Eliezer and Sarah – were poor and elderly, and he was

orphaned at about the age of five. He was adopted and educated

by the local community, but was said to be a non-conformist,

“preferring the solitude of the woods around his hometown,

where he could freely commune with God”(17).

Several accounts indicate that in his teens, Rav Israel worked

first as a school assistant and then as a caretaker at the

local synagogue, presumably in Okup. “At the age of

12 Israel became a helper to a schoolmaster, gathering the

children from their homes in the morning and taking them back

in the evening. On the way he taught them the synagogue hymns…”

(18).

Heppenheimer (19)

suggests a different course of events, whereby Israel left

Okup already before the age of ten, joined a group of holy

men with a mission of “rebuilding Jewish communities

from the inside”, and wandered with them through much

of the Polish kingdom, eventually settling in the town of

Tluste where, by then in his teens, he took a job as a behelfer

(assistant teacher). Encyclopedia Britannica Online (20)

presents a third alternative, positing that the Besht's birthplace

was "probably Tluste, Podolia".

Although it is widely written that Rav Israel did settle

for a time in Tluste, the chronology offered by other writers

is rather different. It is said that Israel spent time in

Brody (mentioned above, approximately 75km northwest of Ternopil,

and quite far from the Okup that Heppenheimer and others describe).

| There he married Chanah

(also written Chana or Hannah), the daughter of local

Rabbi Efraim and sister of Rabbi Gershon Kittover (21).

Some accounts (22).

suggest that this was Israel’s second marriage,

his first wife having died shortly after they married,

when he was 18 or 20. Heppenheimer (23)

claims, alternatively, that sometime around 1720 Israel

married Leah Rachel, daughter of Avraham (or Ephraim),

of Kutow (Kitov).

It is interesting to note the differing interpretations

as to why the couple left Brody. Some writers suggest

that the brother of Chanah (or Leah) considered Israel

to be ignorant, disapproved of the marriage, and was

so embarrassed that he encouraged or forced them to

move elsewhere (24).

Another suggests that Israel deliberately posed as an

ignoramus in order to hide his devotions (25).

|

|

|

|

There seems to be general agreement that the couple moved

to the southern Carpathian mountain village of Kutty (Kitov),

situated about 60km straight line distance west of present-day

Chernivtsi. There, Israel was said to have eked out a living

digging clay and lime (26)

and his wife was said to have run an inn (27).

While living in this remote mountain area for a period of

about 10 years, Israel learned the healing properties of certain

grasses and herbs (28),

and his expertise in medicinal herbs earned him a reputation

as a “ba'al shem”. As he practiced his healing

craft he also began to preach his religious teachings. According

to Spiro: “During this time he studied with a secret

society of Jewish mystics, the Nestarim, and he eventually

became a revered rabbi. He travelled from community to community,

developing a reputation wherever he went as a spiritual holy

man and mystical healer, attracting a huge following.”

(29)

According to some interpretations of traditional legend,

Israel next moved to Tluste, where he worked as a teacher

and, on his 36th birthday (16 September 1734), revealed himself

as the Ba’al Shem Tov, marking the official birth of

the Hasidic movement (30).

For what it's worth, Buxbaum (31)

suggests that the Besht spent four years in Tluste, but that

his revelation occurred in Kitov, three months after his 36th

birthday.

Most scholars and others who buy into the notion that the

Besht was orphaned at a very young age tend to gloss over

an incontrovertible fact: that the Jewish cemetery in Tluste

was the location of his mother's gravestone, bearing 1740

as the year of her death. In other words, the Besht would

have been about 40 years old when his mother died and not

a child of five, as legend would have it. In support of the

former contention, it is probably no coincidence that, in

that same year of 1740, the Besht and his wife moved from

Tluste to the fortress town of Medzhybizh on the Bug river,

some 160 km to the northeast. One can speculate that with

the death of his mother, the Besht would no longer have had

a binding commitment to stay in Tluste; and he may have decided

the time was right to move on.

There are other anecdotes linking the Besht to Tluste (32).

A gentile neighbour is said to have provided straw for the

Besht to sit on while he prayed on a small frozen pond to

the west of the town centre. Shimshon Melzter, a poet from

Tluste, wrote a poem about a conversation between the Besht's

mother and one of his ancestors. While sipping tea, the former

is said to have lamented the fact that the young Israel was

not serious about his studies. Perhaps the Encyclopedia Britannica

Online’s contention (mentioned above) that the Besht's

birthplace was “probably Tluste” is not without

merit.

Finally, some have speculated, somewhat tenuously, that the

Besht may have lived in a house next to a small stream that

meanders through Tluste, bisecting the town's main road. In

support of this conjecture, the large modern

house presently standing on that location is reported

to have been occupied by rabbis who later served in the town.

|

|

In Medzhybizh, the Besht and his wife

had a son Tzvi Hersh and a daughter Udel (or Adil).

The family lived in Miedzyboz for the last 20 years

of the Besht’s life, until his death on 22/23

May 1760. |

|

|

| |

The threads of the Besht’s life

in Miedzyboz are pulled together by Rosman (33),

who examined the town’s tax records in his critically

acclaimed dissertation (34).

The Besht's daughter, Udel, married Rabbi Yahiel Ashkenazi

and had a daugther of her own – by the name

of Feiga – who would later wed Reb Simchah (son

of Rebbe Nachman, one of the Ba'al Shem Tov's leading

disciples from nearby Horodenka). The couple had three

sons and a daughter. The most prominent of these was

Rebbe Nachman (1772-1810) who, like his great-grandfather,

spent many years in Miedzyboz before eventually moving

to Breslov (Bratslav) in the latter part of his life.

Click for a genealogy

chart showing these various family relationships.

As the current entry in Wikipedia

aptly summarises, the younger Rebbe Nachman was born

at a time when the influence of his great-grandfather

was waning, and "he breathed new life into the

Hasidic movement by combining the esoteric secrets of

Judaism (the Kabbalah) with in-depth Torah scholarship.

He attracted thousands of followers during his lifetime

and, after his death, his followers continued to regard

him as their Rebbe and did not appoint any successor.

Rebbe Nachman's teachings continue to attract and inspire

Jews the world over."

Although Rebbe Nachman and his followers became associated

with the town of Breslov, it was in Uman - further to

the east - that he spent his last days. He died there

at the age of 38, having suffered from tuberculosis

for the last three years of his life. In accordance

with his wishes, Rebbe Nachman was buried in Uman's

Jewish cemetery which soon became the site of an annual

pilgrimage for thousands of Hasidim on the occasion

of Rosh Hashana, the Jewish New Year. Severely curtailed

during the Communist era, to the point where the devout

had to visit the grave candestinely, the annual pilgrimage

resumed after the fall of communism in 1989 and has

gathered momemtum in recent years.

In September 2006, it was estimated that up to 20,000

followers would travel to Uman from within Ukraine and

abroad, requiring El Al to operate 18 special flights

and charters to channel the visitors through Kyiv and

Odessa. Click here for an online

account of the event, which appears to be taxing

Uman's capacity to host such a large influx of guests

every year.

Ironically, in the quiet town of Tluste / Tovste –

some 330 km (200 miles) to the west – where Rebbe

Nachman's great-grandfather, the Ba'al Shem Tov, founded

the Hasidic movement nearly 275 years ago, there is

no such annual pilgramage – not even the slightest

recognition that this town on the eastern fringe of

Podolia was the spiritual birthplace of Hasidism.

|

* * *

The information presented above attempts to

tease apart different accounts of Ba’al Shem Tov’s

life as interpreted through traditional legend. While the

detail and chronology may be at odds in places, the major

points that emerge seem to be broadly consistent. The Ba’al

Shem Tov spent an important period of his life in the town

of Tluste, living there for at least six years from about

1734, and solidifying his reputation as a miracle worker and

soul master. Given the Besht’s significant – arguably,

paramount – role in the emergence of the Hasidic movement

in the eighteenth century, it is reasonable to assert that

the Ba’al Shem Tov is Tluste’s most famous resident,

though this fact remains, for the time being, relatively unknown

to the outside world.

Notes:

(1) Heppenheimer, Alexander. 300 Years After His Birth the

Ba’al Shem Tov’s Legacy Lives On. The Jewish Homemaker:

https://www.homemaker.org/shvouot98/cover.html; last accessed

in early 2005 (link not available in September 2005).

(2) Robb, Christina. 1997. Book review of Reaches of Heaven,

by Isaac Bashevis Singer.

The Boston Globe Online. https://www.boston.com/globe/search/stories/nobel/1980/1980t.html;

last accessed on 3 September 2005.

(3) Spiro, Ken (Rabbi). The

Hassidic Movement; last accessed on 3 September 2005.

(4) Anonymous. Meaningful Life Center. Rabbi Israel Baal

Shem Tov (Besht) – (1698-1760). https://www.meaningfullife.com/spiritual/mystics/The_Besht.php;

last accessed on 3 September 2005.

(5) Assaf, D. pers comm. 2006.

(6) Rosman, M.J. Founder of Hasidism: A Quest for the Historical

Ba’al Shem Tov. Berkeley, University of California Press,1996.

pp. 63, 233.

(7) Ben-Amos, D. and J.R. Mintz (eds). Shivhei ha-Besht:

In praise of the Baal Shem Tov. Northvale, N.J., 1993. pp.

36, 211.

(8) International Jewish Cemetery Project: https://www.jewishgen.org/cemetery/e-europe/ukra-t.html;

last accessed on 16 August 2005; Lindenberg, G. (ed.). Sefer

Tluste. Tel Aviv, 1965. p. 38; and Milch-Avigal, S. (ed.).

Can Heaven be Void? Jerusalem, 2003. p. 232.

(9) Isaacs, Mark. Hasidic Judaism and Lutheran Pietism.

https://www.elcm.org/hasidicrelattoPietististicLutheran.html;

last accessed in early 2005 (link not available in September

2005).

(10) Heppenheimer, Alexander. 300 Years After His Birth the

Ba’al Shem Tov’s Legacy Lives On. The Jewish Homemaker:

https://www.homemaker.org/shvouot98/cover.html; last accessed

in early 2005 (link not available in September 2005).

(11) Spiro, Ken (Rabbi). The

Hassidic Movement; last accessed on 3 September 2005.

(12) Baal Shem Tov Foundation. The Biographical Rabbi Baal

Shem Tov (The Besht) 18 Elul 5458 - 6 Sivan 5520 (1698-1760).

https://www.baalshemtov.com/whowashe.htm;

last accessed on 3 September 2005.

(13) JewishGen’ ShtetLinks. Pre-19th-Century Brody:

Hasidism

https://www.shtetlinks.jewishgen.org/brody/brody.htm;

last accessed on 3 September 2005.

(14) Heppenheimer, Alexander. 300 Years After His Birth the

Ba’al Shem Tov’s Legacy Lives On. The Jewish Homemaker:

https://www.homemaker.org/shvouot98/cover.html; last accessed

in early 2005 (link not available in September 2005).

(15) Falling Rain Global Gazetteer Version 2.1

https://www.fallingrain.com/world/UP/0/Okopy.html,

last accessed on 15 April 2007.

(16) Zakharii, R. Borshchiv Town and Vicinities.

https://www.personal.ceu.hu/students/97/Roman_Zakharii/borshchiv.htm;

last accessed on 3 September 2005.

(17) Heppenheimer, Alexander. 300 Years After His Birth the

Ba’al Shem Tov’s Legacy Lives On. The Jewish Homemaker:

https://www.homemaker.org/shvouot98/cover.html; last accessed

in early 2005 (link not available in September 2005).

(18) Isaacs, Mark. Hasidic Judaism and Lutheran Pietism.

https://www.elcm.org/hasidicrelattoPietististicLutheran.html;

last accessed in early 2005 (link not available in September

2005).

(19) Heppenheimer, Alexander. 300 Years After His Birth the

Ba’al Shem Tov’s Legacy Lives On. The Jewish Homemaker:

https://www.homemaker.org/shvouot98/cover.html; last accessed

in early 2005 (link not available in September 2005).

(20) Encyclopedia Britannica Online. Ba'al Shem Tov. https://www.britannica.com/eb/article-9011579/Baal-Shem-Tov;

last accessed on 19 November 2006.

(21) Breslov Research Institute. The Breslov Movement: https://www.breslov.org/bmovement.html;

last accessed on 3 September 2005.

(22) For example, Klausner, Y. The Hasidic Rabbinate, Part

I. Rabbinic Genealogy Special Interest Group (Rav-SIG: Online

Journal), https://www.jewishgen.org/rabbinic/journal/hasidic1.htm

last accessed on 3 September 2005; and Segal, E. Hasidism.

https://www.ucalgary.ca/~elsegal/363_Transp/Orthodoxy/Hasidism.html;

last accessed on 3 September 2005.

(23) Heppenheimer, Alexander. 300 Years After His Birth the

Ba’al Shem Tov’s Legacy Lives On. The Jewish Homemaker:

https://www.homemaker.org/shvouot98/cover.html; last accessed

in early 2005 (link not available in September 2005).

(24) Klausner, Y. The Hasidic Rabbinate, Part I. Rabbinic

Genealogy Special Interest Group (Rav-SIG: Online Journal),

https://www.jewishgen.org/Rabbinic/journal/hasidic1.htm,

last accessed on 3 September 2005; and Anonymous. Spiritual

Stars of the Golden Age. Baal Shem Tov. https://www.saieditor.com/stars/baal.html;

last accessed on 9 February 2010.

(25) Breslov Research Institute. The Breslov Movement:

https://www.breslov.org/bmovement.html; last accessed on

3 September 2005; and Heppenheimer, Alexander. 300 Years After

His Birth the Ba’al Shem Tov’s Legacy Lives On.

The Jewish Homemaker: https://www.homemaker.org/shvouot98/cover.html;

last accessed in early 2005 (link not available in September

2005).

(26) Isaacs, Mark. Hasidic Judaism and Lutheran Pietism.

https://www.elcm.org/hasidicrelattoPietististicLutheran.html;

last accessed in early 2005 (link not available in September

2005).

(27) Buxbaum, Yitzak. The Light and Fire of the Baal Shem

Tov. New York, Continuum International Publishing Group, 2005.

p.82.

(28) Isaacs, Mark. Hasidic Judaism and Lutheran Pietism.

https://www.elcm.org/hasidicrelattoPietististicLutheran.html;

last accessed in early 2005 (link not available in September

2005).

(29) Spiro, Ken (Rabbi). The

Hassidic Movement; last accessed on 3 September 2005.

(30) Heppenheimer, Alexander. 300 Years After His Birth the

Ba’al Shem Tov’s Legacy Lives On. The Jewish Homemaker:

https://www.homemaker.org/shvouot98/cover.html; last accessed

in early 2005 (link not available in September 2005).

(31) Buxbaum, Yitzak. The Light and Fire of the Baal Shem

Tov. New York, Continuum International Publishing Group, 2005.

pp. 77-81, 113, 120.

(32) Sommer, U. pers comm. 2008.

(33) Rosman, M.J. Founder of Hasidism: A Quest for the Historical

Ba’al Shem Tov. Berkeley, University of California Press,

1996.

(34) Lazaroff, Tovah. In Search of the Real Ba’al Shem

Tov. The Jerusalem Post – Internet Edition, 14 December

2000. https://www.jpost.com/Editions/2000/12/14/Features/Features.17392.html;

last accessed in 2004.

|